RMJM’s Russian odyssey  http://www.bdonline.co.uk/story.asp?sectioncode=453&storycode=3119930

http://www.bdonline.co.uk/story.asp?sectioncode=453&storycode=3119930 8 August 2008

By Amanda Birch

Roger Whiteman, principal of RMJM and director of its London office, talks to Amanda Birch about the trials of the practice’s Gazprom HQ scheme, recently renamed the Okhta Centre, in St Petersburg BD: Has the tower has become an unwitting punch-bag for the wider political situation in Russia? I don’t think so. The project is providing a real regeneration opportunity for St Petersburg to be able to look at inward investment to the city, creating more jobs and bringing more wealth and tax revenue. We are looking at how we manufacture things locally, so it has a large benefit to St Petersburg. It was probably a very brave political decision, made as a necessity for the city’s continued success and revitalisation.

How did you feel when Kurokawa, Foster and Viсoly, walked off the jury? We didn’t know anything about it until it was in the press. We know there was a public vote and the public selected our scheme. There was a jury which sat and announced the winner. How, why, who formed the jury and who left the jury is a degree of speculation. If these people didn’t feel that a tall building was the right thing, why did they ask to be on the jury in the first place?

And what about when several thousand Russians protested against your tower? RW: I don’t think it’s as unusual as one would expect. It is something that some people instantly felt very strongly about, including people who have never been to St Petersburg and have no idea what this building looks like and where it’s located. When the building is built, it will show that the right decision has been made.

Wasn’t your confidence shaken? It would be fairly arrogant to say we paid no attention to it and weren’t affected. But St Petersburg has the fourth largest city population in Europe and the numbers that protested were very small compared with the overall population. We just have to stand by the process we’ve been through.

Wouldn’t it have been more of a challenge to design a low-lying building? Both a tower and a low-lying building are a challenge — just very different ones. Of the competition entries, the lower, more solid buildings were of a density that didn’t create particularly good environments. One of the reasons people aren’t developing in the city centre is because the 48m height limit isn’t the scale for modern office buildings.

Won’t the tower still be visible from the eastern part of the historic centre? It’s a little like saying, ‘Can you see Canary Wharf in London?’ If you go down to the river, you can; if you stand in Trafalgar Square, you can’t. When people think of a building at this height, they think they are going to see it at that height and scale everywhere from every single point. But the tower will be 5km from the city centre, and that reduces the size and scale of the building.

Couldn’t a compromise be made on its height? It’s exceeding the height in terms of the brief, but rather than cut the building off and have a flat top which gives it a very harsh line, the top of the building is the spire and comes to a point so that it touches the sky very lightly. Even if we pulled this building down to 150m, I think people would still say it’s a tower. The key was to make sure it doesn’t have an impact on the historic city centre.

Aren’t you concerned about setting a precedent? I think the building will set a precedent for what can be achieved in terms of high-quality, well designed buildings — one that says, ‘Guys, if you want to build here, set your levels of expectation as high as you can.’

But won’t this mean more mediocre towers as well? Cities can’t afford to build that many tall buildings. In a city like St Petersburg, where you only build up to 48m, you cannot put modern office buildings into them.

You can’t increase the density — and you can’t afford to do that outside the city centre and be able to afford good public transport as you need a level of density to do that.

One of the reasons St Petersburg has been in decline for 15 years is because the city centre is being held as such an untouchable space. So the city is now looking at how to develop outside the city centre. This site is an old industrial brownfield site close to the city centre, but it is outside Unesco’s world heritage site.

It’s in an area that will allow for natural further regeneration of the industrial areas around it. But there are no other skyscrapers in the masterplan. The city believed the scale of the buildings along the edge of the River Neva, which is huge, could be higher because if you maintain the scale of the buildings as they were in the historic city centre, those buildings become almost inconspicuous.

Does Unesco have the power to lower your tower? I don’t believe the final decision rests with Unesco. Any comments it makes have to be ratified by the country’s government.

Is Unesco overstepping its authority? I think Unesco, like English Heritage, has a place in the consideration of how we develop. It seems to have a format that allows it to speak out and hopefully provide checks and balances for modern development without hindering it.

How does the design respond to the harsh climate? The climate in St Petersburg is very hostile and very variable. It goes from minus 30 to plus 30, and changes very quickly. Almost two-thirds of the year is a harsh climate, perhaps like Toronto, then it gets very hot in summer, with a climate similar to Dubai’s. What we’ve done with this building is to create a fur coat which captures air between two skins of glazing.

How does that work with the extremes in temperature? In the winter, that air zone captures the warm air and it supplements the heating. So the heating and the air pass through that zone and draw the warm air out, which goes into the building. In summer, when that zone heats up, it has vents in the outside walls so that the air moving around the building naturally draws out the hot air. Rather than the zone warming up, it actually keeps the building a lot cooler. I don’t think anybody has done it on a building of this size and scale.

It sounds expensive.

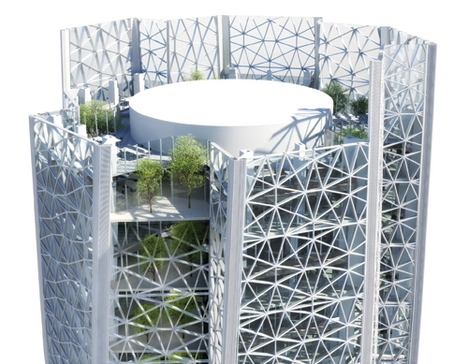

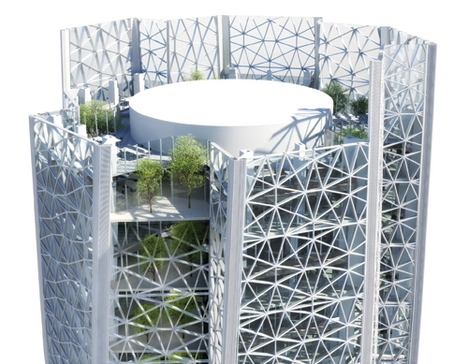

Yes. The envelope is designed so that the building looks fairly complex on the outside. We started off with a very simple circular core with five rational squares around it — inspired by the original pentagon-shaped Swedish fortress.

Each of those squares, as it goes up through the building, is on the same axis. As it moves out and comes together to the point, it rotates 90 degrees through the height of the building, but always stays as a square. This means the office spaces are a very efficient 15m x 15m with atrium spaces between them, which means that every office looks out into an open space and gets natural daylight.

We found that a grid made of triangular shapes allowed us to pick up changes in the direction of the wall. These panels slot together with a slight rebate between the two, so they pick up the differences as the plane warps and twists, giving the building this gentle, sinuous shape.

How do you cope with a marshy site like this? We are testing two types of foundations — pile foundations and a barrette piling system, which is a series of friction-bearing concrete fin walls. These have a larger surface area that has more contact with the marshy ground and this provides a more stable base.

We are actually building two or three barrettes and two or three piles, then we shall look at what’s it like to construct them under the conditions of the soil and what loads they can take.

What is the planning situation? It’s slightly different from what we’ve got in the UK. There’s an approval to the masterplan, and recently a public hearing took place to review amendments to that plan. The next approval is for construction, which will be submitted at the end of this year.

Are Russian standards more stringent than the UK’s? The whole philosophy is different. The first step is to get the local authority’s approval in terms of the aesthetic quality. Our competition entry was evaluated by the city and the client, and that became the basis on which the documentation develops.

We then go into what’s called the “P” stage, which stands for project, and is like UK Building Regulations approval. In Russia, you have to submit all the information up front on all the systems, some in a greater amount of detail and some in lesser detail. But you have to get approval before you can start construction.

How much say does the national government have in the project? Any building over a certain size has to be evaluated by the federal government. Everything below ground gets approved locally in St Petersburg, while everything to do with the building above ground gets approved in Moscow.

There are also special experts we have to liaise and agree with because many of the building regulations don’t exist at the moment for a building of this height and size anywhere in Russia. They are starting to rewrite the regulations in Moscow for tall buildings at the same time that we are designing our building.

Are you planning to design more towers in Russia? I don’t have any preconceived ideas on what the next project is and how we design it.

The biggest challenge is working in a foreign country and producing buildings of international quality to local standards. I think the design and the approach will be more challenging than the actual construction.

Once the systems are approved, people know how to build, but it’s convincing people that the right solution is there and that it meets all regulations.

Power struggles -

Water Gate The site chosen for the Gazprom tower has always been important historically — it has water on two sides and thus forms a key gateway to the main fluvial arteries of St Petersburg. It has undergone many transitions and often served as a site for fortifications when the city was under attack.

Pentagon Control of this strategic hub and the surrounding land is long contested by Russia and Sweden, and a Swedish fortress, Landscrona, occupies the site as far back as 1300. Another Swedish fortress, Nyenskans, is built there in 1611 in the form of a five-sided star to maximise views for defensive purposes. This fort falls to Peter the Great in 1703, who then creates his namesake city nearby.

Sweet Corn RMJM is the only UK practice on the six-strong shortlist to design the HQ for Russian energy giant Gazprom. Others in contention include Massimiliano Fuksas, Herzog & de Meuron, Rem Koolhaas, Daniel Libeskind and Jean Nouvel. In December 2006, RMJM wins the contest with its proposal for a Ј1.2 billion, 396m-tall tower, which is dubbed “the Corn on the Cob”.

Bitter Blow As the winner is announced, it emerges that three of the judges — Norman Foster, Kisho Kurokawa and Rafael Viсoly — walked off the competition jury and boycotted the contest. Kurokawa states his reason for leaving was his opposition to all six shortlisted schemes and his belief that St Petersburg should preserve its low skyline.

Rem delirious In early 2007, Rem Koolhaas, one of the unsuccessful finalists, calls on architecture’s superstars to join him in a campaign to overhaul the competition system in the light of the Gazprom controversy. He condemns the system both as “hideous” and as a drain on resources and influence. Tony Kettle, RMJM managing director, mounts a passionate defence of his firm’s Gazprom design in BD.

World Shaker In September 2007, Unesco threatens to strip the city of its world heritage site status if it proceeds with plans to build the 67-storey tower.

On the March Also in September, several thousand people, among them architects and heritage campaigners, march through the city protesting against the skyscraper, which they claim will “destroy” St Petersburg’s famous skyline.

They shall not pass In December, RMJM locks horns with Unesco by making a defiant pledge to protect

its plans for Europe’s tallest building. RMJM resists pressure to scale back the height of the tower, and instead only replaces a wave-shaped building at its base with five asymmetric glass pavilions gathered around it in a “fractured” design.

Never let it be said In January 2008, Unesco denies press reports that it no longer has concerns about the impact of the tower on St Petersburg, claiming it has been misrepresented, while by May, it signals that the city could retain its world heritage site status even if RMJM’s controversial development goes ahead.

Bits and pieces In June, Unesco is dubbed “oblivious” to St Petersburg’s future after a leaked report reveals that the international body will stop short of recommending that the city’s world heritage status be revoked, but will instead say that the historic centre should be put on its list of “endangered” heritage sites. Colin Amery, a former head of the World Monument Fund in Britain, says Unesco should act with greater urgency if the tower is to be halted.

Where there's a will The renamed Okhta Centre — named after a river in St Petersburg — is set to be completed by late 2011.

News Master

News Master